MEDIA

Behre: The name Lincolnville is the first and surest sign this SC town is different

Sep 24, 2022

Syndicated and guest columns represent the personal views of the writers, not necessarily those of the editorial staff. The editorial department operates entirely independently of the news department and is not involved in newsroom operations.

-

Button

Pernessa Seele unlocks the door to Wesley Methodist Church where she was raised; she now owns the building. After years of living in other states, she has returned to Lincolnville and aims to spread the word about its unique history. Robert Behre/Staff

By Robert Behre rbehre@postandcourier.com

LINCOLNVILLE — This small town may be South Carolina’s least understood, most unique historical place. Its relative anonymity stems partly from its tucked-away site along railroad lines where Berkeley, Charleston and Dorchester counties meet up, partly from its small size, and partly from its origins during one of the most tumultuous chapters of the state’s history, Reconstruction.

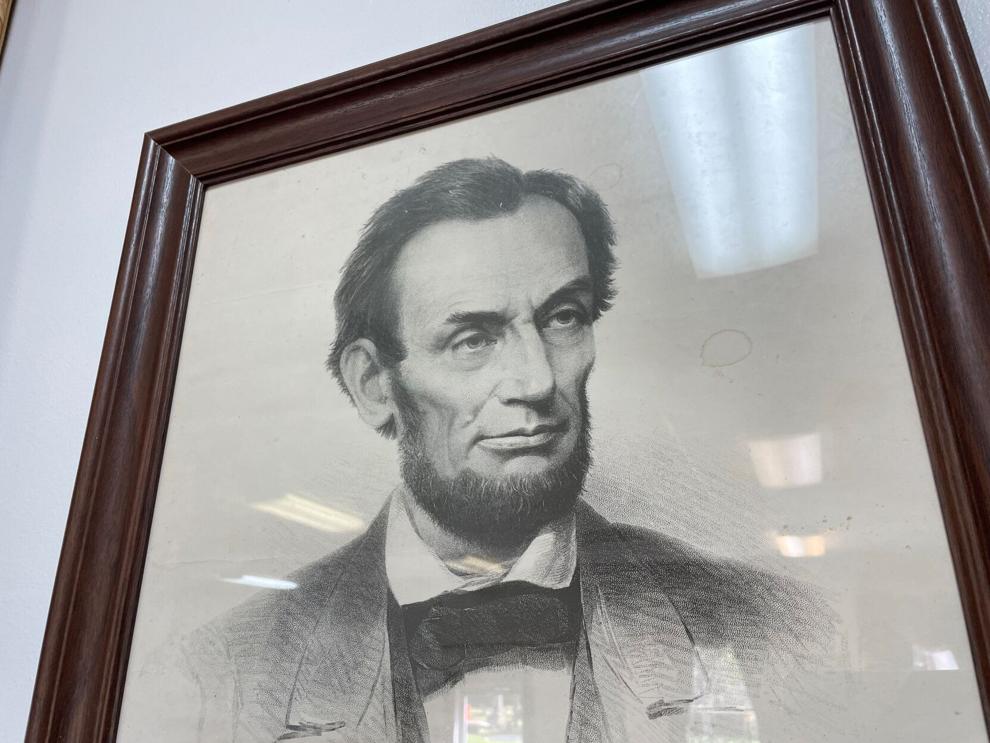

The town, which I’m guessing is the state’s only public place named in honor of President Abraham Lincoln, didn’t merit an entry in the South Carolina Encyclopedia — not even in the index. Many people who live in the Charleston region don’t even know where it is.

-

Button

This image of Abraham Lincoln might be the only such image hanging inside a council chambers in South Carolina, but this president is who Lincolnville was named for. Robert Behre/Staff

By Robert Behre rbehre@postandcourier.com

But Pernessa Seele, whose ancestors helped found this incorporated African American town and who grew up and went to school and church here before moving away for work, hopes to change that. She seems uniquely positioned to do so. Her professional experience includes having founded and run The Balm in Gilead Inc., a 33-year-old Virginia-based nonprofit that works with faith communities in the United States and in the United Republic of Tanzania in East Africa to reduce health disparities.

“Lincolnville and its history live in me. It’s in my blood,” she says. “Lincolnville has just been sitting here waiting for me to come back and get busy.”

-

Button

Pernessa Seele stands in an old Lincolnville cemetery; she reached out to historic preservation students with Clemson and the College of Charleston’s joint program for help evaluating its condition. Robert Behre/Staff

By Robert Behre rbehre@postandcourier.com

And she has. She still hasn’t moved back full time, but she has founded the Lincolnville Preservation & Historical Society and printed brochures and newsletters to share the town’s story. She has reached out to the Clemson’s Graduate Program in Historic Preservation for help documenting and assessing the town’s Bible Sojourn Cemetery and one of its most curious surviving buildings. And she has plans for a historical park as well as walking and biking trails that would make the town’s past more accessible to present eyes.

While many people driving along U.S. Highway 78 south of Summerville might notice a Lincolnville town limits sign, it’s hard for passing motorists to appreciate what’s here, particularly beyond the town hall at 141 W. Broad St. (originally the 19th-century Williams Graded School, a Rosenwald School) that was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980 but suffered a severe fire two years later. It was rebuilt as the Town Hall in honor of former longtime Mayor Charles Ross.

-

Button

The building housing Lincolnville’s Town Hall originally was built as a Rosenwald School, and markers celebrate that chapter of its history as well as the town’s longtime mayor. Robert Behre/Staff

By Robert Behre rbehre@postandcourier.com

The town’s story began just two years after the end of the Civil War when U.S. Rep. and Emanuel AME pastor Richard Cain led a group of seven black Charleston men, all of whom were likely frustrated with their treatment in the city, to find a place for a new community they could call their own. They found a site along the train line about 20 miles north of Charleston and spent $1,000 to buy 620 acres from the railroad. The tract was known as “Pump Pond” and formed a perfect circle around the stop where the train’s engineer could get fresh water.

Unlike many other 19th century settlement communities, Lincolnville incorporated in 1889 and survives to this day as a local government still led largely by African Americans, many descended from the town’s early generations.

-

Button

The cornerstone of the 19th century Wesley Church can be a considered a metaphor for Lincolnville: Its past survives, but you have to look a bit harder to identify it. Robert Behre/Staff

By Robert Behre rbehre@postandcourier.com

Not many historic-looking buildings survive in Lincolnville, but one that does is the town’s 1933 jail, a tiny stucco structure off Smith Street with two cryptlike cells. Clemson students plan to study its condition and recommend preservation steps.

-

Button

Lincolnville’s historic jail survives and might be one of the smallest ever built in South Carolina, being little larger than a standard garden shed. Robert Behre/Staff

By Robert Behre rbehre@postandcourier.com

Seele’s efforts scored a recent success, with the National Park Service adding the town to the Reconstruction Era National Historic Network, a series of national places that related to the 1861-1900 Reconstruction Era, “one of the most fascinating and misunderstood periods in American History,” in the agency’s words.

Ultimately, Seele hopes Lincolnville will become a tourism destination for all those coming to Charleston interested in African American history. Until it does, expect her to remain busy trying to make it so.

“I tell folks when I was 17, I was running away from my mom’s house,” she says, “and now I’m running back.”

-

Button

This depiction of Wesley Church, one of Lincolnville’s two main houses of worship, hangs in Town Hall. Robert Behre/Staff

By Robert Behre rbehre@postandcourier.com

-

Button

While Lincolnville has a host of buildings that survive from its 19th century beginnings, it also is seeing some new construction, such as these homes near town hall. Robert Behre/Staff

By Robert Behre rbehre@postandcourier.com

The Lincolnville Preservation & Historical Society

The Lincolnville Preservation & Historical Society

Built By FourDeep